Fishing for Gold in the Nautical Gothic

July 24, 2024

By Sarah Comyn

Opening with a professor waving ‘his arms around magnificently’ in the ‘dusky’ scientific laboratory of the University of Otago, the gothic tones of the pseudonymous short story, ‘The Gold Fisher’ (1897) are apparent from the start. Published in the Cromwell Argus, the story follows the student Ebenezer Grookin as he is inspired by the professor to consider the inexhaustible wealth of the ocean:

the very water of the ocean contains gold, one grain to every ton—to every ton—and just think of the thousands, the millions, of tons of sea water, rolling and tossing eternally, spouting high against the towering cliffs of rocky shores, tons of it shooting up into the air with resistless force—and a grain every ton; lap lap-lapping softly against the ‘silver strand,’ dark and horrific under the open sky.

Like his etymological ancestor, Ebenezer Scrooge, Grookin is consumed by the pursuit of wealth. For Grookin this obsession is directed towards the gold that can be found, according to his esteemed professor, in the depths of the ocean. While the other students ridicule Grookin and the professor, joking they should ‘float a company to exploit the Pacific’, Grookin is clearly captivated by the prospects of the professor’s repetitive ‘grain to every ton’ ‘lap lap lapping’ and sets off on a journey to an abandoned island.

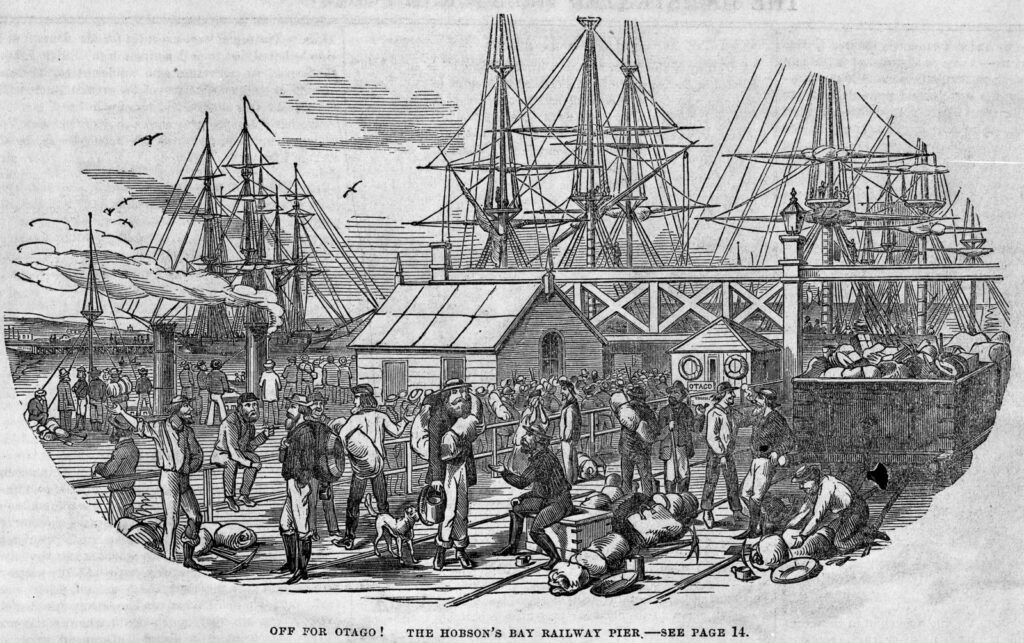

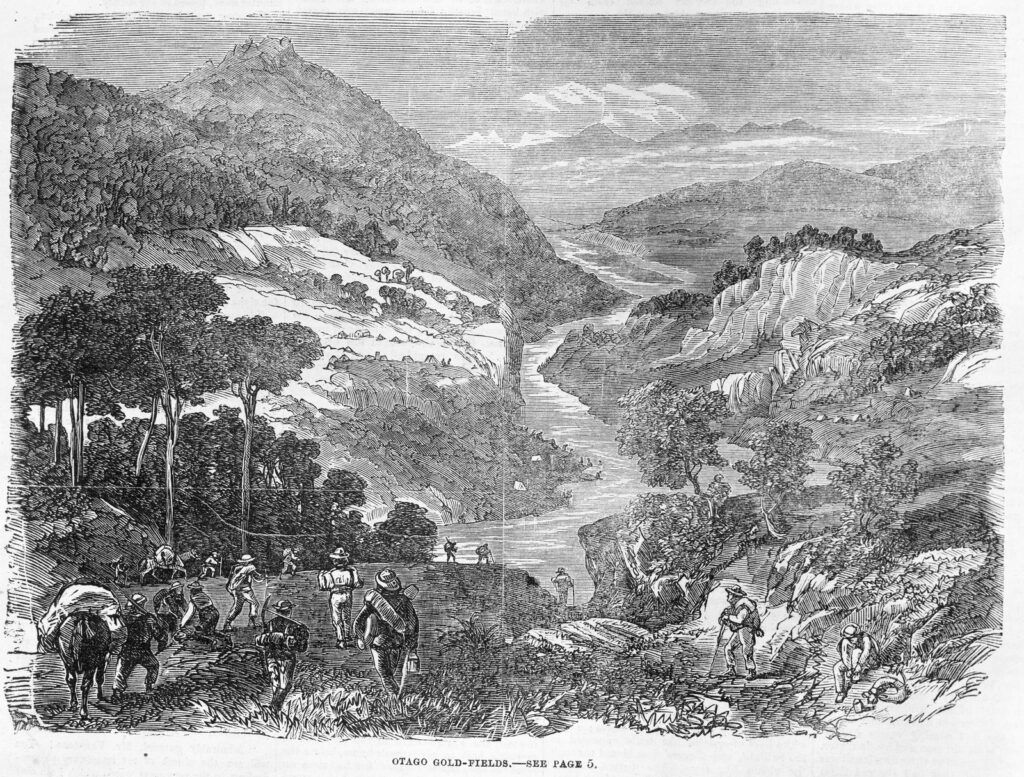

With this setting, Grookin’s pursuit enters the realm of the nautical gothic where, as Jimmy Packham and David Punter reminds us that ‘to think about oceanic depths is already to think in gothic terms’. Through the nautical setting the story also seemingly challenges the ‘land-bias’ not only of gothic literature, but of mineral mining (Adler). Grookin does not dig for gold; rather he fishes the ocean’s depths, unlocking its secrets: ‘Knowing the secret of its composition, Grookin would be able to force the sea to disgorge the wealth it contained, and, as he truly shouted, the world was his.’ The nautical setting allows for the isolation of Grookin the gold fisher—‘human companionship was the last thing he wished for’—while also drawing attention to the differences between Grookin’s solo pursuit and the romanticised ‘mateship’ and community of the land-based goldfields.

Grookin’s solitary activity is interrupted by the arrival of a pair of diggers. It is here that Grookin’s oceanic gold fishing is transformed from an apparently harmless obsession into a monstrous one. While spying on the pair (who still remain unaware of Grookin’s presence on the island), Grookin overhears them speaking of a recent American discovery where ‘one o’ them scientific blokes, has found out a way o’ makin’ gold with chemicals an’ stuff…Takin’ the bite o’ grub out o’ the mouths o’ thousand o’ hard workin’ diggers, an’ their wives, an’ kids’. Horrified by the alchemical association of his labours and what it would mean for ‘hard workin’ diggers’ and their families, Grookin’s night becomes filled with the terrors of starving women and children haunting his solitary gold fishing:

Thousands of women looking eagerly, imploring to thousands of husbands for bread which, alas, they could not give; and clinging to these haggard women, thousands upon thousands of children with their faces pinched and pale, stretching forth their hands unceasingly and crying ‘Bread, mammy, bread, I’m so hungry!’ and the voice of their wailing rushed through the air like the roaring of a tempest, and the din of it filled the world…And then these thousands of haggard, hunger-worn faces turned towards him, and from their deep sunken eyes the sufferers shot at him glances of undying hate, of maternal ferocity, of childish complaining, and a forest of bony hands rose in the air, some clutching at him as if to tear him to pieces, some raised fiercely to Heaven as if curses were being dragged down upon him…

The sea in which Grookin was searching for gold now becomes a sea of skeletal hands trying to catch hold of and punish him for his scientific experiments in gold mining. Even though the intellectual and scientific labour of Grookin’s oceanic explorations and its mental and physical cost is apparent in his altered appearance—’shaggy-haired, red-bearded, freckle-faced man danc[ing] madly on the shingle, flinging his arms wildly’—the narrative draws a stark contrast between Grookin’s labour and that of the land-based heroic miners ‘toiling in old mines, finding new ones, pressing into strange regions where they alone ventured, suffering all kinds of privations and hardships, daring and doing all things in their search for gold—these thousands of bold enterprising men would be ruined at a stroke’ by Grookin’s ‘gold net’ being made public. Despite the ‘amalgam [being] the secret that had cost so much thought and so many experiments’, Grookin’s mental labour can never compare to the physical labour and hardship of land-based miners. Faced with the prospect of destroying the livelihood of these miners through his scientific discoveries, Grookin chooses to destroy all his records and tools, instead throwing his lot in with the pair of diggers who he leads to the land-based gold he had already discovered on the island prior to his oceanic experiments.

While fishing in the monstrous depths of the nautical gothic, the short story ultimately re-establishes the land-bias of mineral mining through its celebration of the romanticised mateship of heroic diggers who battle with the earth, rather than the sea.

Works Cited

Alder, Emily, ‘Through Oceans Darkly: Sea Literature and the Nautical Gothic’, Gothic Studies 19, no. 2 (2017), 1-15.

Huia, ‘The Gold Fisher’, Cromwell Argus, 26 October 1897, p. 3.

Packham, Jimmy and David Punter, ‘Oceanic studies and the gothic deep’, Gothic Studies 19, no. 2 (2017), 16-29.