A Letter of Grievances from a Chinese Miner in the Asylum of Colonial Melbourne

August 18, 2025

By Ge Tang

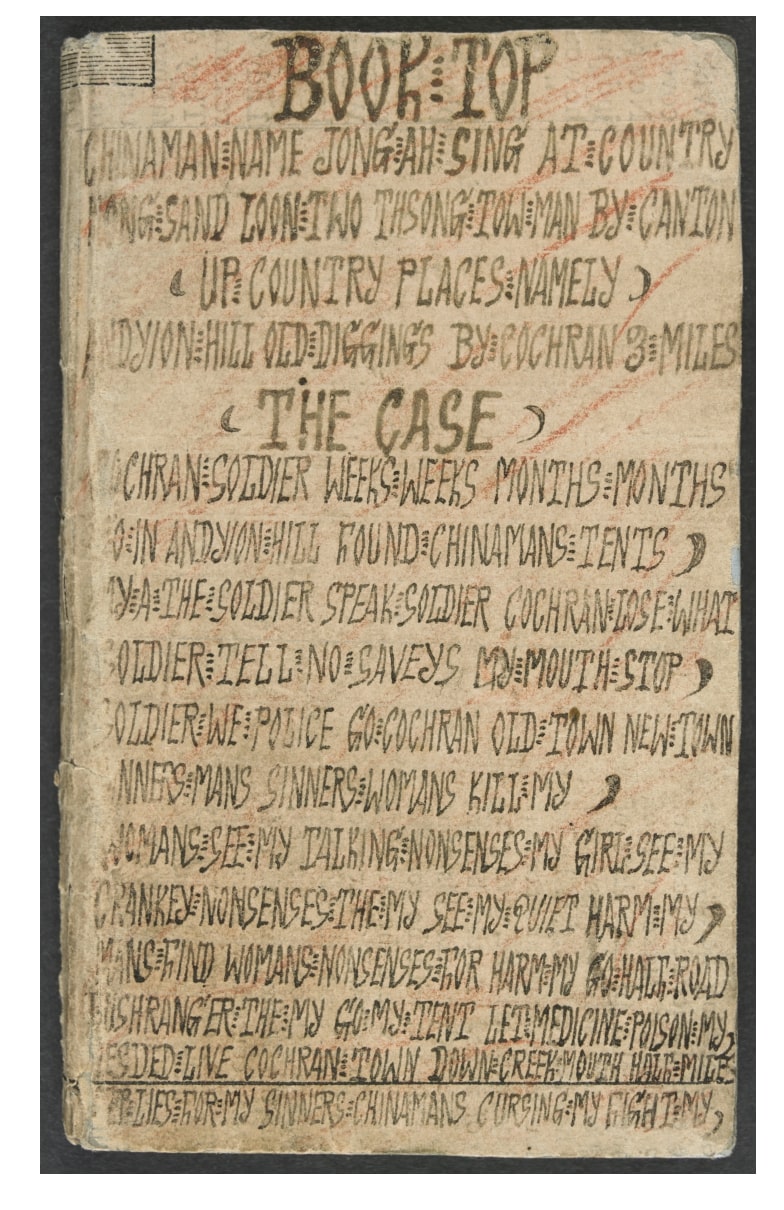

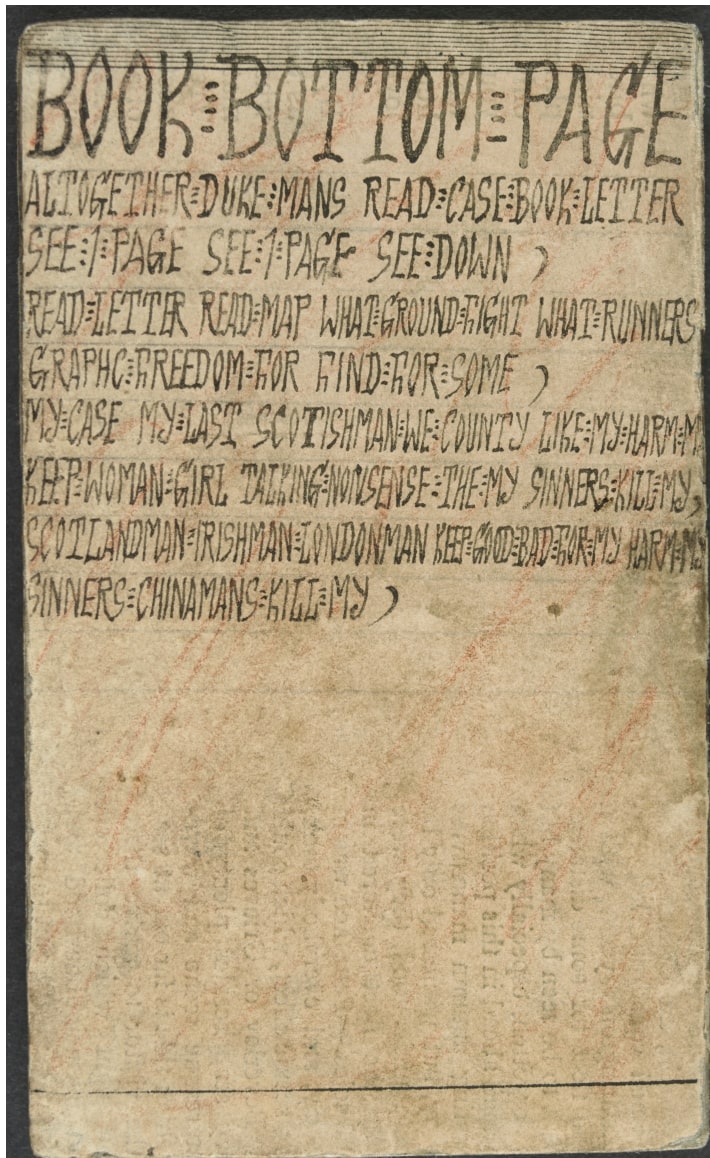

I learned about ‘The Case,’ an English-language letter of grievances by Jong Ah Siug (1837–1900), a Cantonese miner in the goldfield of Victoria, while finishing my PhD in Melbourne. Its peculiarity and the questions it raises about the writing of diaspora, the literary culture of extractivism, and the boundaries of what constitutes Australian and Anglophone literature were among the primary reasons that drew me to Dr Sarah Comyn’s ‘Minerals’ project. The unusualness of this letter is striking at first glance (Fig. 1): it is written in block letters, with words joined by three vertical l dashes, and takes the form of a palm-sized bound book, with its front and back covers being marked as ‘book top’ and ‘book bottom page’ (Fig. 2). A Cantonese grammatical structure reveals itself almost immediately to my ear, trained as it is to this tonal rhythm, despite the differences between the Cantonese spoken by Jong and that spoken today and the regional variations in this language.

Fig. 1. Front cover of Jong’s book. Image Courtesy of the State Library of Victoria.

Fig. 2. The back cover of Jong’s book. Image Courtesy of the State Library of Victoria.

In 1855 Jong migrated from ‘Fong-sand’ (香山, present-day Zhongshan) to Victoria during the gold rush at the age of 18 and worked in the diggings in central Victoria. Jong wrote the letter in English in the hope that the colonial authorities could understand the abuse and hostility he suffered while living on the goldfields, in particular his account of a knife fight which led to his mistreatments in the hospital and his incarceration in gaols. His ultimate goal was to vindicate himself and to bring those who wronged him to justice. To help his addressees understand his case and to validate his testimony, Jong provided four hand-drawn maps of the places he referred to in his narrative:

(1) the Chinese camp where the fight occurred;

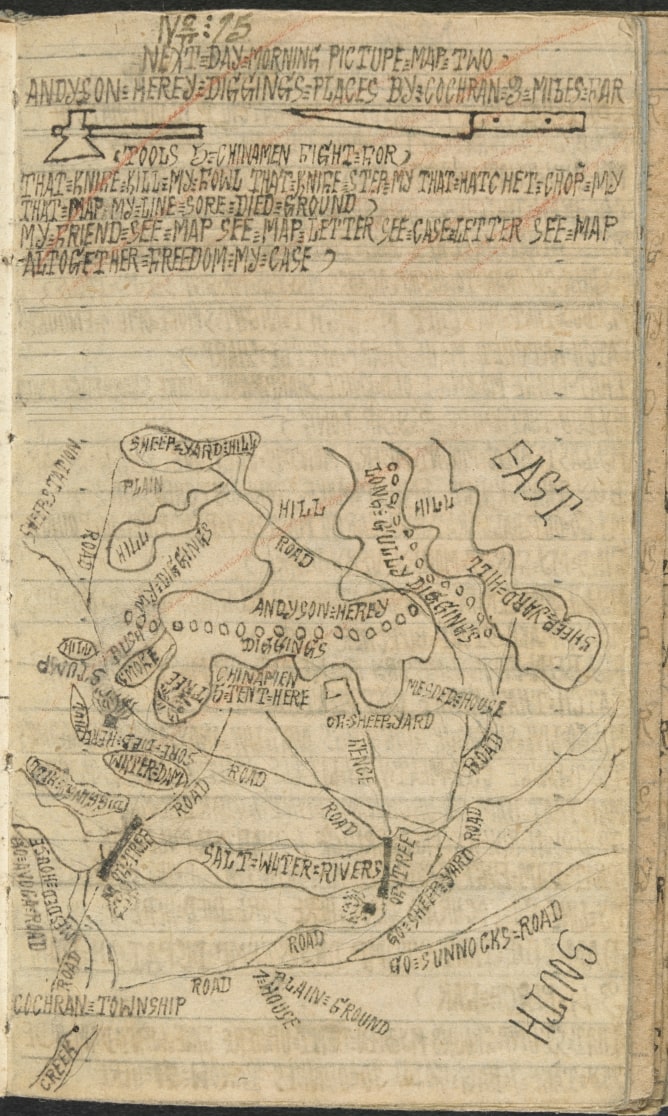

(2) Anderson’s Hill, where the Chinese camp and his shaft were (Fig. 3);

(3) the townships of Dunolly, Cochranes and New Cochranes; and

(4) the Dunolly hospital.

His determination to petition in a foreign language is particularly remarkable if we consider his reliance on scribes for writing his family letters (‘The Case,’ p. 21).

Fig. 3. Page 15 of Jong’s book. Image Courtesy of the State Library of Victoria.

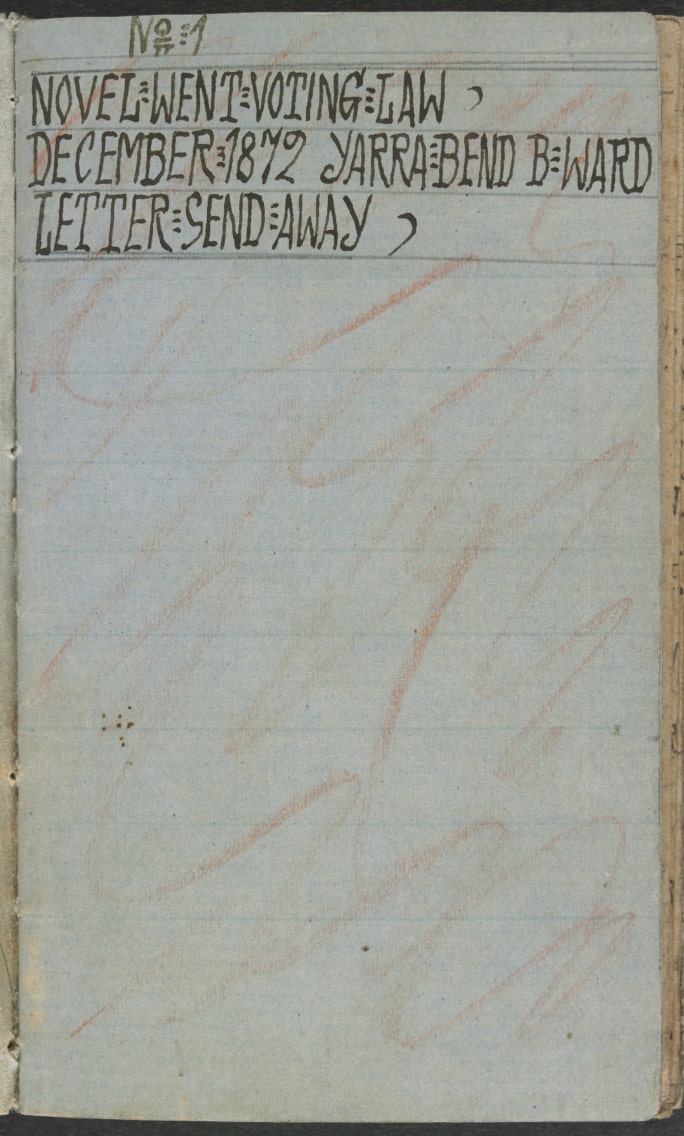

On the first page of his letter (Fig. 4), Jong dated it December 1872, indicating that he wrote it while incarcerated in Ward B of Yarra Bend Lunatic Asylum in Melbourne (Fig. 4). Jong clearly intended his work to be seen, declaring that its ‘novel’—meaning the content of the letter (which can be inferred based on his use of the same word elsewhere in the text)—supports or follows ‘Law.’ Jong does not specify a recipient for his letter, instead addressing various authorities, including the ‘governor,’ ‘parliament,’ ‘high judge,’ and ‘Duke mans.’ I suspect that ‘Duke mans’ represents his phonetic approximation of dài-rén (大人)—a respectful term to address officials in his home country. At times, however, Jong shifts tone and refers to his addressees as ‘friends,’ demonstrating an effort to elicit sympathy

Fig. 4. Page 1 of Jong’s book. Image Courtesy of the State Library of Victoria.

Jong’s grievances concern both Europeans and his fellow countrymen. For a sense of it, we can have a look at the cover page (Fig.1), where Jong lists key episodes of distress:

- Frequent visits from the local police force to the Chinese camp where he lived, which reflects the strict surveillance placed on Chinese communities at the time. Jong expresses hurt feelings over the dismissive way his questions were answered, highlighting a power dynamic that left him feeling vulnerable.

- [European] Women and girls made fun of (‘talking nonsenses’) and even ‘harm[ed]’ him, seemingly because he remained ‘quiet’ and unprovoked. Jong’s account later reveals that these rumours concerned his desire for a wife, or even multiple wives— polygamy was then in practice in his home country and the Chinese diggers migrated without their wives and struggled to find partners in the goldfields.

- Physical violence from [European ]men.

- A bushranger attempted to poison him.

- The Millstead family (an Irish family) spread rumours and wronged him.

- Jong was verbally bullied and physically attacked by Chinese ‘sinners,’ who his narrative later reveals to be his Chinese neighbours involved in the knife fight, including Sheteen and Ah Key. This last complaint forms the core of his case book.

Jong’s narrative suggests some disputes with Sheteen and Ah Key, which escalated into a knife fight, leaving both sides wounded. Sheteen and Ah Key subsequently sued Jong for assault, leading to his arrest and trial in the Dunolly police court. According to the coverage of the trial in the Dunolly and Bet Bet Shire Express on July 18, 1868, two doctors (Doctor Wolfenden and Doctor Green), who were sent by the court to evaluate Jong’s mental state, agreed on Jong’s ‘unsound mind.’ They made the diagnosis despite their shared observation about Jong’s moments of lucidity, which they dismissed as temporary. The judge acquitted Jong on the grounds of lunacy, but he was retained in imprisonment and was later transferred to the Melbourne Gaol. From Jong’s narrative, we know that in the gaol, he made repeated pleas to people he encountered there for a new trial in Melbourne. He asserted his innocence, arguing that his rivals provided flawed and biased statements. After an attack on the wardens of Melbourne Gaol, he was transferred to Yarra Bend. It was there that he wrote ‘The Case,’ continuing his plea to the authorities to look into the knife fight and his other sufferings prior to and during his incarceration.

Jong’s little book is well structured. It comprises five distinct parts:

(1) the introduction of the people involved in the fight;

(2) the lead-up to the fight which occurred on the previous day;

(3) the weapons used in the fight;

(4) the fight itself and its aftermath, including the trial and his transfer between the hospital, goals, and the asylum; and

(5) a summary of his appeals.

The division between these parts is indicated by the remaining space on the page where Jong concludes each part. Furthermore, the structure within each part is equally clear. Jong explicitly signals the change of topics by using a recurring sentence structure at the end of each subsection: ‘All conclude, and down […] for.’ By this, Jong means that he has completed his account in the current part, and in what follows, he shall talk about a new subject, with him placing for after the name of this subject to indicate what he refers to.

The remarkable structure of Jong’s narrative suggests his sanity—at least during the drafting of the book, and in turn affirms its legitimacy both as a personal testimony and as a petition to the government. However, the unusual semantics of his English vocabulary and grammar make his letter difficult to comprehend, even if it did reach its intended recipient. According to sociolinguist Jeff Siegel (2009), ‘The case’ features a mixture of standard English, Chinese pidgin English, and Australian and Pacific pidgins (328–30). Jong’s limited English vocabulary —his 16,102-word letter, contains only ‘approximately 800 different lexical items’ (316)—imposed significant constraints on his capability to convey his grievances in a way that was accessible to his addressees. This challenge accounts for the unusual semantic meanings of his lexicons. For instance, in his letter, freedom carries a meaning similar to understand clearly. In Figure 3, Jong appeals to his addressees—his ‘friend’—asking them to ‘see map, see map letter, see case letter, see map, altogether freedom [his] case’ (page 15). While we can infer what Jong hoped to convey by freedom by examining how he uses the word throughout the text, many other words are more difficult to decipher.

I haven’t been able to find evidence about how local authorities responded to Jong’s petition. He was transferred to Sunbury Lunatic Asylum in 1879, where he remained in confinement until his death in 1900 (Moore and Tully, 63). His letter was gifted to the State Library of Victoria in 1880, by Henry P. Fergie, a parliamentary agent, as ‘a literary curiosity’ (Moore and Tully 1). Jong’s appeal and legal demands were thus likely incomprehensible to the readers the letter may have reached at the time.

‘The Case’ remained in obscurity in the library for over a century, until two historians, Ruth Moore and John Tully, deciphered and transcribed it into accessible English. Their translation and supplementary materials were published in a single book, titled A Difficult Case: An Autobiography of a Chinese Miner on the Central Victorian Goldfields (2000). The publication represents a sincere scholarly effort to bring Jong’s voice to the world and has contributed immensely to public and academic attention toward his letter. Yet, owing to the complexity of Jong’s writing, mistranslation and misinterpretation seemed inevitable in any attempt to translate ‘The Case.’ Indeed, Xu Mao (2023) has noted numerous errors in their translations as a result of linguistic and cultural barriers, arguing their flawed translation has created a negative image of Jong and risks affirming the poorly supported idea of Jong’s insanity (756). If Jong’s peculiar English, as Mao has reminded us, ‘makes any reading an uncertain interpretation,’ then misreadings of Jong’s story are inevitable. This raises a question for anyone who seeks to understand subaltern lives like Jong through their voices when they do speak. Jong’s writing represents a potent example of the many texts of an inherently cross-cultural and multilingual nature in the literary history of extractivism which brought together people of diverse ethnicities and cultures. How can we do justice to these voices which seek to be understood and place an ethical demand on us—yet may lie beyond our full comprehension—without What can we learn from Jong’s peculiar form of life writing in rethinking and redefining literary culture which was produced in the goldfields?

The Structure of Jong’s book*

*Here, I have provided my provisional summary of ‘The Case,’ but in fear of misreading, I refrain from translating Jong, and instead only indicate what each part is about.

Cover page. It contains Jong’s autobiographical notes and an abstract for the mistreatments he received.

Part One (pages 3–8) serves as an introduction to the people involved in the conflict, including himself. He narrates, one by one, when he and his neighbours moved to Anderson’s Hill, the relative location of their tents, their financial situations, and their relationships. Remarkably, he draws a map of the Chinese camp to visualise his textual narratives. These details aid our understanding of what he believes to be the causes of his neighbours’ ill feelings towards him, but they are also helpful, at least for me, in understanding his version of the fight and assessing the credibility of his narrative. For instance, the relative location of their tents helps determine whether it would have been possible for him to overhear conversations in a neighbouring tent.

Part Two (pages 9–13) describes the night before the fight. Jong lays out the disagreements between him and his neighbours, which contributed to their feelings against him.

Part Three (pages 15–18) describes two tools involved in the fight, a knife and a hatchet. He provides a sketch drawing for both, but he also includes a map of Anderson’s Hill (Fig 3). The map shows the location of his shaft (‘my diggings’) and other sites relevant to his movements after the fight, such as the location of the tree where he fainted from blood loss. His narrative starts on the next page with a heading: ‘hatchet, knife and map: 3 thing letter.’ Jong explains where and why he bought the hatchet and knife, as well as their original purposes. Ending this part on page 18, Jong states, ‘All conclude, and down fight for,’ indicating that this part is finished and he shall proceed to describe the fight.

Part Four (Pages 19–54) covers the fight and the aftermath, comprising clearly structured subsections. In pages 19 to 28, with a heading of ‘next morning letter,’ Jong details the day of the fight, which occurred the day after the night he depicted in Part Two. Apart from recalling the fight and describing his wounds, Jong also notes the arrival of doctors and the police. Then pages 29–41 cover Jong’s confinement in lock-ups and his treatment at the Dunolly hospital before his trial. He complained about the food in the goal, his European doctor who he distrusted, and the wardens who ridiculed and hurt him. On page 41, roughly one-third of the way down, Jong marks the end of his account of pre-trial confinement with this line: ‘All conclude, and down, 4 police court for, 1 session for.’ As he promises, Jong moves on to describe his appearances in court, and his experience of waiting for a jury court session that he requested (pages 41–46). After the trial, Jong was kept in Maryborough Gaol before his transfer to Melbourne Gaol. He describes his distress there on pages 47–53: he was forced medicine, his pigtail was cut, he was hit by the wardens, and he was bullied by other prisoners. He also details his unsuccessful suicide attempt, after he lost hope for a new trial. The chapter concludes with his transfer to Yarra Bend, where he wrote ‘The Case.’

Having offered a detailed account of the knife fight and the subsequent injustice and sufferings he endured, in Part 5 (Pages 54–78, with a jump between page 59 to page 70), Jong summarises his grievances (in a way more detailed and comprehensive than in the abstract) and appeals to the authorities for help and justice. The heading at the start of this, ‘Find Law, Find Warrant, Catch Mans’, written in larger lettering, translates the urgency of his demands.

In the Book Bottom Page, Jong articulates one last, impassioned plea for help. He asks his addressees to patiently examine his case report, page by page, and to study both the text and the maps.

Works cited

Jong, Ah Siug. Diary. MS 12994. The State Library of Victoria, Australia.

Mao, Xu. ‘Sanity at the mercy of language: Interpreting the “nonsense” of a Chinese miner in Australia.’ Journal of Postcolonial Writing 59.6 (2023): 754–67.

Moore, Ruth, and John Tully, trans and eds. A Difficult Case by Jong Ah Siug: An Autobiography of A Chinese Miner on the Central Victorian Goldfields. Daylesford: Jim Crow Press, 2000.

Siegel, Jeff. ‘Chinese Pidgin English in Southeastern Australia: the notebook of Jong Ah Siug.’ Journal of Pidgin and Creole languages 24.2 (2009): 306–37.