Writing from Below: Petitions by Chinese Indentured Laborers in the South African Mines

September 20, 2024

By Ge Tang

In various imperial contexts—whether in the British Empire, the United States, or Canada—mineral extraction was indebted to the labour of imported workers. These labourers often did not speak the local language; few had sufficient reading and writing literacy in their mother tongue. These raised several important questions: How did they document their experiences and grievances in foreign and often hostile environments? What forms of writing did they use? Did they bring any home culture of self-fashioning that shaped their writing in the mining fields? How does their writing provide insights into their lives and reflect their agency?

Guided by these questions, my research trip to South Africa focused on the petitions submitted by Chinese indentured miners working in the South African mines from 1904 to 1910. The majority of these labourers were from northern China, primarily from peasant and rural backgrounds. Forced by a combination of natural disasters and social unrest following the Boxer Uprising, they sought work in South Africa as a means of survival and to support their families. The Foreign Labour Department (FLD) was established to oversee the employment of the Chinese labour force in the mines, and to enact protection of their rights and well-being such as wages, accommodation, and medical provisions. For this purpose, FLD set up mailboxes at the mines’ pay stations where the Chinese could submit complaints and petitions to appeal for help and interference from FLD.

In the FLD archives housed in the National Archives of South Africa in Pretoria, I found two big folders of papers (FLD 240 and FLD 241, Figure 1). The papers in the folder are further organised into individual files based on the mines where the petitioners were employed (Figure 2). FLD 240, for instance, labelled ‘Chinese Complaints,’ contains files from 76/1 to 76/15. Among these files, File 76/7 contains complaints from the Wit Deep Gold Mine. All the original complaints and petitions are understandably written in classic Mandarin. The FLD hired several Chinese clerks, who could extend language assistance, while FLD’s inspectors of the mines were alleged to master certain levels of Chinese proficiency.

Figure 1: FLD 240, ‘Chinese Complaints’, Files 76- 76/15.

Figure 2: Complaints by Chinese, Wit Deep (Limited), File 76/7, FLD 240

The file folder includes not only the complaints themselves, but also government correspondence for instance, between the FLD’s superintendent, secretary, and inspectors, revolving around addressing and solving individual petitions. Some petitions are accompanied by translations and investigation reports by inspectors as well as testimonies gathered during the inquiries.

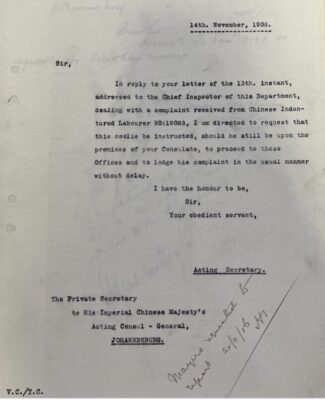

Not all petitions were submitted through the mailbox system. Some Chinese workers, likely harbouring distrust, petitioned through the Chinese consular based in Johannesburg. For example, a Cantonese worker from the Kleinfontein Mine petitioned the consul to be transferred to another mine owing to bullying by northern Chinese workers at his current location. In response, the FLD directed the secretary to write to the acting consul-general, advising that the petitioner ‘lodge his complaint in the usual manner without delay’ (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Petitions from Chinese workers employed at the French Rand Gold Mine. File 76/10, FLD 240.

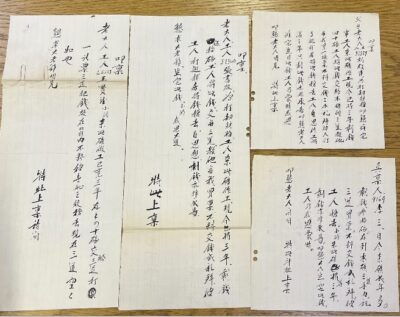

Given the limited literacy of most indentured labourers, I’m not surprised to see that petitions signed under different names display identical handwriting. One scribe drafted individual petitions for four Chinese workers at the French Rand Gold Mine (Figure 4), all of whom pledged, likely against the Chinese policeman or the mine controller, for withholding their hard-earned wages (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Petitions from Chinese workers employed at the French Rand Gold Mine. File 76/10, FLD 240.

These petitions show several prominent features shared by other Chinese petitions in the FLD archives. First, they are written vertically from top to bottom, with the columns arranged from right to left on the page, following traditional Chinese writing conventions. Second, these petitions adopt normative etiquette, diction, and format reflective of petition culture in Qing China. Of the four petitions (except for the one on the bottom right), three begin by invoking the traditional gesture of deep respect and submission—’叩禀’ (kowtow petition). In the petitioners’ culture, one kneeled and touched the ground with one’s forehead to express utmost humility before an authority figure to whom one made a formal appeal. Referring to the inspector—an FLD clerk responsible for looking into their cases—as ‘老大人’ (respected superior), a title imbued with reverence, the petitioners aimed to establish a relationship of submission in the hope of gaining favour. After thus addressing the inspector, these four petitions unfold in a format widely adopted by others in the FLD archives. We are provided with the petitioner’s passport number followed by his name; the petition then briefly describes the mistreatment and wrongs suffered, ending with a plea for help. This format enhances the formality of the petitions. While this formality allowed labourers to utilise the FLD’s established channels to express their grievances, it also imposed constraints on how they conveyed, often at the expense of individuality and the more emotionally charged aspects of their experiences. The fact that petitioners with limited literacy had to rely on scribes also raises questions about the embodiment of agency in these petitions.

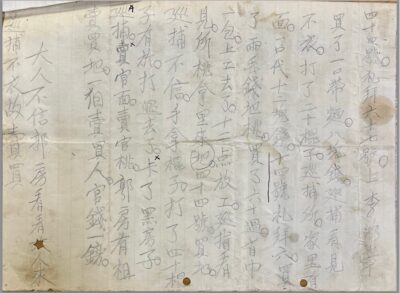

However, there are also less formal petitions that blend casual, everyday language with some formal elements. One petition from Nourse Mines Limited stood out for its plain and rambling style (Figure 5). The petitioner, in a conversational tone, recounts his experience (translated as follows to the best of my ability):

(I work in) Mine No. 44. On Saturday, along with someone from Mine No. 67, I went to (a store called) Li Hongzhang and bought a bag of flour for eight Rands. The policeman saw this and didn’t approve. He hit me with 20 strokes. At the police station, he sells (or they sell) flour for 20 Rands a bag.

On Saturday the 14th, I bought some peaches for 20 cents. I got 60 peaches and a towel. I went to work, and at 12 o’clock, I was off work. The policeman saw the peaches and asked, ‘Where did they come from?’ I told him that (I, from) Mine No. 44, had bought them. The policeman didn’t believe me and hit me, with over 40 strokes. (Afterward,) I was locked in a dark room.

The policeman is selling official flour and peaches. In the police station, there is a trader, and (they exchanged) one pound of official money.

If you, my respected superior, don’t believe me, go and check the room yourself. Let’s see if the policeman will keep selling when you arrive.

Figure 5. A Chinese petition from the Nourse Deep Gold Mine. File 76/16, FLD 240.

As evidence of his limited written literacy, the petitioner used a number of homophones—words with similar pronunciations but different meanings. Interestingly, a later reader, maybe a scholar who consulted the archive as I did, marked the letter to note spelling errors, not comprehensively though. In addition, unlike other documents, it bore fingerprints and other marks of pollution. These material aspects invite us to consider the condition of the writer, and the arduous journey this document took to eventually reach the FLD. Despite its informality, this petition compelled official action. In the file where I found it, it is accompanied by a detailed two-and-a-half-page investigation report, indicating that the FLD sent an inspector to look into the case.

For the Chinese miners, who had no access to conventional literary forms to publish their stories, these petitions served as vital expressions of their experiences and grievances. They are not merely historical records, but powerful life writings that illuminate and illustrate human experience and indenture under extractive capitalism. I am currently in the initial stages of sorting these materials and look forward to sharing more findings as my research progresses.