Gothic Gold Mining: Psychological Horror in ‘A Hunt for a Gold Mine’

October 27, 2023

By Katie Donnelly

‘A Hunt for a Gold Mine: A Lunatic’s Christmas Ramble in the Land of Tasman’, is an Australian gothic tale, published anonymously in the North Australian in 1886. The short story is recounted by an unnamed narrator, presumably a white settler, on his journey through the land of Tasmania in search of a gold mine. Driven by a romanticised desire for fortune, the narrator leaves his “humdrum life of a clerk” in favour of the “halo of romance” surrounding the gold-hunting lifestyle (6). His eventual isolation in the wild Australian landscape is entirely self-provoked by this sense of greed and ignorance of mining labour. However, the text’s depiction of his gradual psychological decline is also highly racialised in its direct relation of his madness to his increased exposition to the “primitive” indigenous land and its natural extremities. The uncanny setting of the tale is derived from the narrator’s obvious sense of whiteness within the racialised landscape, indicating the author’s use of the gothic in a process of estrangement that highlights Australia’s cultural and geographic difference from Britain and Europe.

From the narrator’s arrival in Tasmania, descriptions of the barren landscape are palpably gothic. With a strong emphasis on the severe sensory impact of the climate, the land itself is villainised as an inflictor of pain on the unacclimatised body of the narrator. This in turn creates an interesting dynamic between the untamed landscape and the civilised body, who inhabits it. Unaccustomed to Australian life and land, the narrator’s non-indigeneity causes him to become victim to the harsh environment:

Hard walking was a novel experience; in my thin-soled boots, it was positive torture, with every step, I sank to the ankle in the imponderable dust, which, working into the interstices of my knitted socks, caused me exquisite agony. My feet were raw and galled within a very short time (6).

This passage draws a stark contrast between commodity culture and nature, as the sophisticated and well-dressed man becomes the “foreign other” in Australia. Here, the narrator’s items of luxury are rendered torturous under the crude conditions of the land. It is ironic that the author emphasises the pain that the narrator’s clothing causes, rather than the natural conditions themselves. His material commodities are of no benefit and he is consequently stripped of his class-based attire, which apparently cannot exist within the Australian bush. Accordingly, it is his inexperience and sense of white foreignness that occasions disorientation, provoking his psychological decline. As his journey progresses, his gradual descent into madness coincides with his further seclusion into the wilderness. Influenced by his recent reading of Marcus Clarke’s For the Term of His Natural Life, the narrator describes his second day’s travels as a combination of “weary plodding and panoramic horror” (6). Clarke’s classic Australian novel that portrays the horrors of convict life has clearly impacted the narrator’s projection of anxiety onto his current environment. The panoramic vastness of the scene enables this projection and paradoxically produces the gothic trope of claustrophobia. As Roslynn D. Haynes has demonstrated in her analysis of the Australian desert, the most alarming prospect faced by explorers coming from the confines of heavily populated Britain and Europe, was that of void: repeated vistas of empty horizontal planes under a cloudless, overarching sky. These vast expanses of apparently empty space became paradoxical symbols of Gothic enclosure and entrapment (77). The Australian wilderness thus becomes a panoramic version of British gothic’s claustrophobia of confinement. In this text, the landscape’s boundlessness facilitates a projection of hallucinogenic and hypnotic qualities. The narrator’s panoramic view, in combination with his foreign perspective, thus becomes a gothic component of psychological delusion.

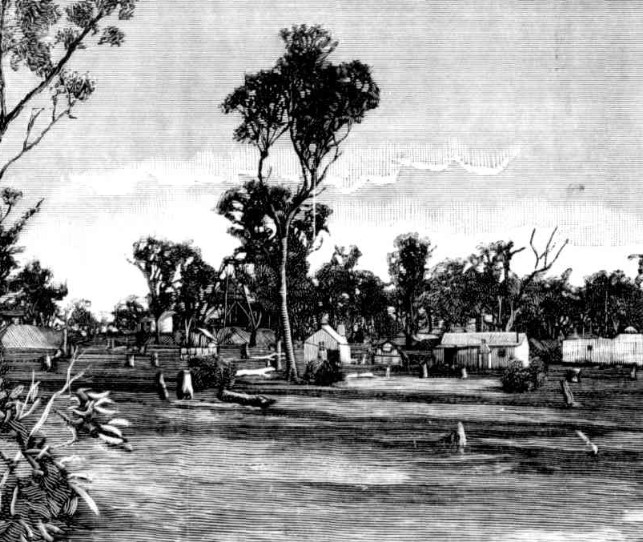

The text’s Christmas setting adds to this gothic atmosphere, coinciding with the Victorian tradition of telling yuletide ghost stories. A direct reference to Ann Radcliffe’s Mysteries of Udolpho in the narrator’s description of a rustic church “amid dark foliage” highlights the text’s adoption and translation of European gothic conventions onto a specifically Australian context (6). Moreover, another Radcliffean trope is evident in the feminisation of the masculine narrator against the rugged landscape. Under the isolating conditions, the narrator himself comes to resemble the trope of the vulnerable gothic heroine. These transpositions of European gothic onto the spectralised Australian wilderness are described by Ken Gelder as “imported concepts”, contributing to the theme of “the explorer who never returns” (380). Although the narrator survives and ultimately returns to society without having struck any gold, Gelder’s idea of imported gothic is still relevant here. Specifically, the narrator’s depiction of the intricate pathways and winding forestry of Tasmania are clear derivatives of the traditional maze-like gothic castle: “the ringed and blasted gumtrees, like skeletons whose dry bones glistened in the rays of the setting sun, gave a weird and spectral appeal to the landscape” (6). Instead of supernaturally inhabited buildings, the land itself becomes a spectral entity, manipulating its appearance to the vulnerable foreigner, who perceives the natural flora and fauna of Australia as skeleton-like. Gina Wisker similarly states that if the gothic genre serves as an attempt to defamiliarize the familiar, the Australian gothic is even more uncanny in its destabilisation of the common haunted house trope, instead constructing images of abandoned mines and emptied out towns that draw on settler perceptions of the “harshness of the land” (297). In this text, the haunted landscape transcends the traditional haunted house in its inherent vastness and gothic enthrallment of the narrator’s mind.

Similar to European gothic, there is a close connection between physical space and mentality evident in the text. In this case, the haunted landscape and the narrator’s haunted mind are parallel. The further the narrator strays from human-inhabited land and social communication, the more disorientated he becomes. The symbols of telegraph wires and tram lines are significant as the only evidence of human life in the rough landscape, and are also important in highlighting the narrator’s self-inflicted exile:

The uncanny-looking vegetation which fringed the tram-line waved and rustled its dusty foliage in a ghostly manner, stirred into goblin life by the evening breeze which whispered and moaned like the voices of departed spirits (6).

By the tale’s conclusion, the landscape has completely adopted the narrator’s frame of mind. As he contemplates his isolation from his family and reminisces about their usual Christmas festivities, the scenery externally manifests this loneliness, with the wires representing his lack of communication. The text’s landscape subsequently conjures these metaphorical images of departed spirits to represent his distant family members. On account of the narrator’s intense solitude, he becomes a ghostly figure himself, departed from his own homeland. With this in mind, he acts as a spectral outsider, threatening the indigeneity of the Australian landscape in terms of both his spectral foreign identity and his initial intent to exploit the land and acquire gold. The text therefore provides a gothic contemplation on white greed for gold versus the harshness of natural landscape.

Works Cited:

‘A Hunt for a Gold Mine: A Lunatic’s Ramble in the Land of Tasman’, The North Australian, 29 Jan 1886, p.6.

Clarke, Marcus. For the Term of His Natural Life. London: Richard Bentley and Son, 1897.

Gelder, Ken. ‘Australian Gothic.’ A New Companion to the Gothic, edited by David Punter, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2012, pp. 379-392.

Haynes, Roslynn D. Seeking the Centre: The Australian Desert in Literature, Art and Film. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Radcliffe, Ann. The Mysteries of Udolpho. Ed. Bonamy Dobree, Oxford University Press, 2008.

Wisker, Gina. ‘Australian and New Zealand Women’s Supernatural and Gothic Stories 1880-1924: Rosa Praed and Dulcie Deamer.’ Women’s Writing: The Elizabethan to Victorian Period, vol. 29, no. 2, 2022, pp. 295-318.